The emergence of Spring seems to have halted for a few days here in the northeast of Switzerland. Fog and low temperatures create the chilly atmosphere of being in a massive refrigerator. People here in Waldstatt chat about the weather like everywhere else, and locals reassure me that wonderful weather is coming next week. I am fine with the cool, damp days, though. The energy is very good for meditation and contemplation.

Many people who know me are aware that I spent quite a few years as a monk in Zen Buddhist temples. One question that people quickly ask me is, “Why did you leave?” Honestly, I used to be offended by this question, since I doubted that the people asking me about a very difficult transition in my life had grasped why I had come to live as a monk and why I stayed so long in the monastery. We were discussing my very personal relationship to Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha, and not the weather. Perhaps it felt like a stranger asking me about a former marriage and wanting to know why I divorced a wife I had loved very deeply.

I have come to understand better why people spring towards the end of my monastic story. It is not easy to be patient in understanding our challenging lives, or anyone else’s. Many of us have a monk or nun in us that would like to take a good chunk of life in a remote place to go within, supported by like-minded people. It also suits most people better to let go of this idea and commit fully to our lives right where we are in the world.

For me, going to a temple was not an experience to put in my pocket and say, “That was interesting, what’s next!” It was an incredibly challenging chapter of my life, where I built powerful relationships to places and people that deepened over time and shaped my being profoundly.

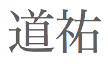

A big part of my ordination was accepting the Zen Buddhist community as my family. It was a true act of ‘leaving home’ and this ritual was highly impactful, emotionally, psychologically, and energetically.

Leaving home….what does it really mean? In 1985, I certainly wanted to get away from the materialism and deeply engrained attitudes of collective and individual self-centeredness that reigned in the USA as I knew it. I had been a History student in Europe in 1983-1984 and lived in a country with a wall down the middle of it. I had visited many Eastern European countries with a fondness for Marxism during that time. What I saw during those visits was poverty, pollution, and guns. I had never been exposed to those things, which weakened my enthusiasm for socialism/communism.

At university in the city of Göttingen, I was constantly confronted by students to explain the American perspective on the issues of the time: the Philippines, Nicaragua, El Salvador, stationing nuclear missiles in W. Germany, and more. There were many important topics, and I was not at all a master of debate in those days.

When I returned to the States, Ronald Reagan was re-elected as president in a landslide. But it seemed to me that the American public showed almost no interest in critical discussion of major international issues. Simplistic Cold War rhetoric was enough for almost everybody around me. But the superficiality of mainstream thinking about social issues in my generation was frustrating. There was so much suffering out there, much of it a result of decisions made by Americans like myself. And there was so much maturing to do, work to do on myself, so I might feel useful in a very complicated world. Or, was I becoming a crazy person? In any case, at home, I felt like an alien.

Alienated but still hopeful, I was able to get a one-way ticket to Japan after graduation. My plan was to saturate myself in things Asian. While still a teenager, I had encountered an Indian sage, J. Krishnamurti, and had met a Buddhist monk from Sri Lanka in a university course. I had read many spiritual books. I was exposed to Zen and began to meditate on my own in hopes of dropping off my neurotic thoughts on the path to discover the heart of selfless service. These influences came from the East. After losing faith in any healthy socialist or communist developments at home or in Europe, I wondered if societies in the East might be healthier than mine. I could teach English in Japan to earn money, and eventually see all of Asia. This was my hope. I had to leave home.

After becoming initiated in Aikido and the shakuhachi (bamboo flute) and traveling around Japan for a couple years, I had seen enough of modern Japan. Almost all people there were content with the materially based life that I had already experienced as a youth in Southern California. I yearned to touch the depths of the oriental soul and thus, could no longer motivate myself to teach English to adults and children addicted to video games, canned coffee, and manga.

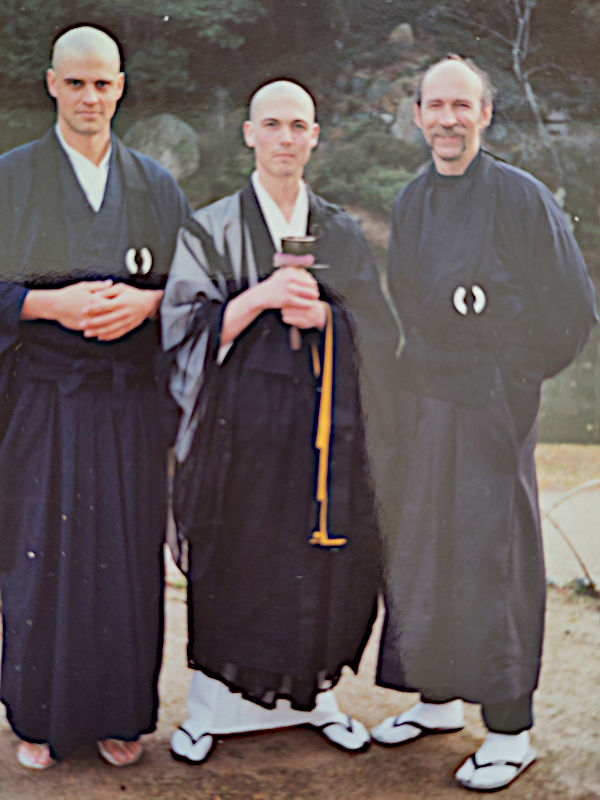

In my second year in Japan, I traveled down to Hiroshima. On the way, I chanced upon a temple in Okayama. I pulled out my bamboo flute to play a few notes and saw an elderly priest with a Yodo-like aura taking a walk. His dog came to greet me. A conversation ensued. He told me foreigners were doing Zen training there. My Japanese at that time was not good at all, but something very important was communicated. A door was opened.

A year later, I thought of the temple where I met the remarkable old monk and where foreigners trained in Zen Buddhism. I made a short visit. My next visit was longer. Six months later, I moved into the Sogen-ji temple.

I cannot say that I consciously searched for that temple or wanted to become a monk. These things happened after my hopes had ripened into a commitment, a vow, and I was ready to sacrifice a good chunk of my allotted life-energy to the Zen master, the teachings of the Buddha, and the Zen community. This initiation meant an abrupt end to reliance on material or emotional support from ‘home’.

I am trying to put down my hopes and experiences in the temple in a book form, perhaps a novel. Images and descriptions are better at communicating whatever has transformed within me than explanations. Something left home during that time in the temple. Something can now see and persevere in a way I couldn’t before. But for the mind that wanted a perfect world, or to become more perfect myself, there was only ‘Great efforts, no results’. Do you know this?

I actually have little natural talent for anything meditative. However, being a good meditator did not turn out to be the heart of the training. The Zen master helped me grow healthy roots in my being, that a tree with some good fruit might have a chance to grow. The Master gave me the name of Do Yu, ‘the way of Abundance.“

So, this is a bit of why I went to the temple and why I stayed fifteen years.

Still wondering why I left?

Yes, I left home again, and it was difficult!

Evidently, I had enough hope and intensity at that time to take a step beyond the temple world and remain true to my quest to become useful and content with my activity in the world. The world outside the monastery is not in better shape, and it has not been easy to adapt to it again. But, many years after leaving my life in the temple, in the cold and fog of my village home here in Switzerland, my tree continues to grow, and fruit ripens. Oh, and good weather is coming!